Capturing a Solar Eclipse

On May 20, 2012, I had a rare opportunity to witness a solar eclipse. This was an annular solar eclipse, meaning that the moon is further away from the earth and produces a “ring of fire” as it crosses the sun. I traveled out west for a summer internship, and I’ve been living in Santa Fe, NM with Simon Mehalek. The two of us took great interest in both witnessing and capturing this astronomical event.

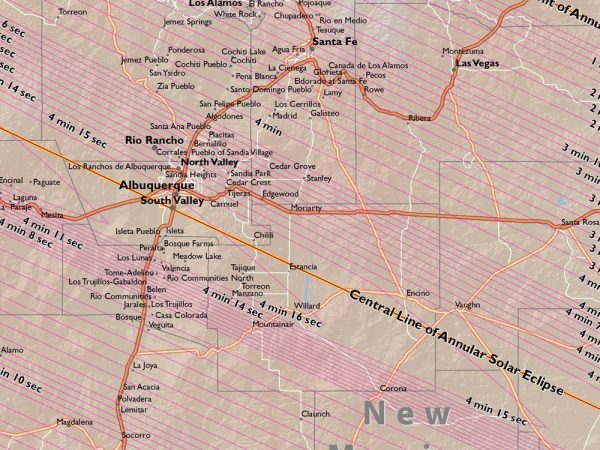

Luckily for us, we were already perched on the side of a mountain with a very clear view of the horizon, and Santa Fe was right in the middle of the totality range. We were scheduled to see the eclipse just minutes before sunset.

Here’s how we made the most out of this once-in-a-lifetime event:

Equipment List:

- Nikon D70 with Nikon zoom Lens EDIF

- Quickset Gibraltar Tripod

- 17-inch MacBook Pro

- USB Extension cable.

- Mini USB interface cable.

- Pelco Industrial Pan & Tilt.

- Two Bodine DC motor controllers.

- Mounting flange.

- Cable and interace to Motor Controllers.

- Nikon Camera Control Pro 2

Last night we got to work planning with projectors as we had our mini command center operational. We had web pages up that charted the path of the eclipse, and we figured out the optimal time to see the eclipse. We had all our computers running looking up information, and a rough plan was hatched to drive down south to get in the perfect positon to see it as the moon crossed(transited) the sun. I initially noticed that Albuquerque, NM came up as one of the best places in the U.S. to see the eclipse, and there was even an animation that demonstrated the how the eclipse would look.

This morning, Simon called one of his friends who is a metal fabricator for some welding goggles, so that we could safely view the eclipse. He was kind enough to loan us some dark glass that was used in welding hoods. This meant instant experimentation holding the glass up in front of cameras and human eyes to view the celestial event.

Phase II: We set out to put our setup together. First, we tried to control the D70 camera from an Android phone or iPhone. This seemed promising, but required hardware we didn’t have, namely a IR LED or a custom USB cable. Rather than hacking a custom USB cable or using an IR LED in the volume port of mobile device (where the audio would have been what modulated the IR LED so that it triggered the remote sutter on the camera), we decided we would go with Nikon Camera Control Pro 2. This required setting up a laptop tethered to the camera to control it.

We put together a Quickset Gibraltar Tripod. Pretty much a military grade tank of a tripod that could hold up a small baby elephant. Set on top of the Tripod is a Pelco industrial Pan & Tilt system that uses 110v DC motors. We had some Bodine Motor controllers floating about, and set to work wiring an aphenol 9 pin circular connector to interface with the pan and tilt.

I was working on testing the photographic gear with the #10 and #9 welding glass by taking experimental photos as the eclipse was just starting, using my iPhone and the Nikon D70. The results were promising, so I spurred Simon on to hurry up and finish the wiring interface for the pan & tilt controller.

We wired up 3 extension cords from the house to the look out spot on a rocky hill by our house that has wonderful vistas of the Cerillos, Orteiz, Jemez, Sandias, and Sangre de Christo mountains. We installed the tripod and mounted the Pan & Tilt control head onto the tripod, attached the camera with a 1/4-20 bolt, and carried the equipment to our designated shooting spot.

Next we dialed in the location for the camera to point at the sun and experimented with the exposure, camera settings, etc. Next we tried the Nikon control interface. Once we had the F-stop and the shutter speed cranked up to maximum, we started the time-lapse intervalometer photographic control to shoot every 5 seconds.

Meanwhile, we were frantically looking through the image directory as the shots were coming in from the camera to see if it was properly exposed. After a few adjustments and setting up the optimal position of the cameras vector, we let it shoot away. Each time the camera took a picture, it automatically saved the image file to the host computer controlling the camera (i.e. the MacBook Pro).

I even managed to get some great shots with my iPhone, with the help of the welding glass we used to protect our eyes.

The final time-lapse images were imported into Adobe Premiere CS5, which has the ability to interpret images as a sequence. This quickly allowed us to view the resulting images as a fluid video. With a little bit of tweaking to select the best parts of each sequence and remove erroneous stills, we created the incredible time-lapse video that introduced this post.

1 Comment

Nice job guys!

About Me

Hi, I'm Neil! I'm passionate about building delightful products at scale, creating music, and performing in theatre and comedy shows.

Leave a Comment